Is diet soda any healthier than regular soda?

People can’t get enough information about artificial sweeteners. Do they help you diet? Do they make you fat? Are they healthier than sugar? Are they healthy?

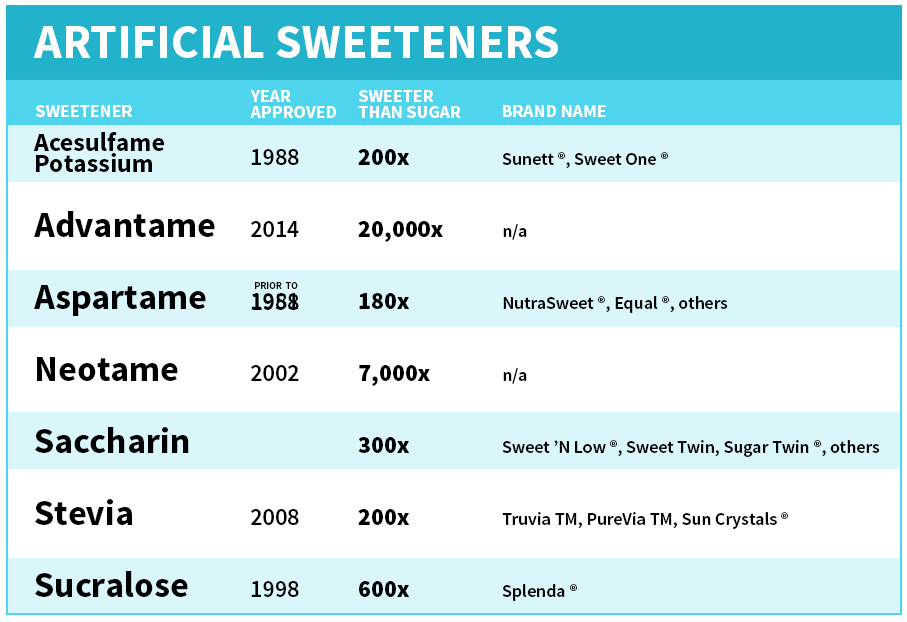

Six artificial sweeteners have passed toxicology tests and been deemed safe by the Food and Drug Administration: saccharin, aspartame, acesulfame potassium, sucralose, neotame and advantame. These go in the diet drinks and sugar-substitute packets we know so well — saccharin is Sweet n’ low, aspartame is Equal, acesulfame potassium is Sweet One and Sucralose is Splenda. Why then do people, especially parents, approach artificial sweeteners with caution?

Just because something is safe doesn’t necessarily mean it’s healthy. Tests used by the FDA are designed to find “gross abnormal outcomes” in a lab setting, said Susie Swithers, a neurobiologist at Purdue University. They are “not necessarily designed to look at small cumulative effects that may only be seen if you look over decades of use.”

For example, table sugar (the combination of fructose and glucose) is mostly safe to consume. Your body needs glucose to survive. But of course, too many cupcakes and cookies can lead to weight gain and disease. Sugar in moderation may be safe, but in excess, it’s unhealthy.

Data from Food Insight

Still unclear is whether it’s healthier to swap sugar for sugar substitutes. Recent research shows that artificial sweeteners are not inert – they alter human metabolism and gut bacteria and may be linked to Type-2 diabetes.

It’s helpful to understand how the body processes diet drinks and Splenda-sweetened lattes. When sugar substitutes enter the mouth, they activate sweet taste receptors on our tongue. The activation of those receptors tricks the body into thinking it’s about to consume sugar, and the body releases hormones to digest that sugar, Swithers said. But the sugar never arrives.

Recent research suggests that artificial sweeteners are not completely harmless – they alter human metabolism and gut bacteria and may be linked to Type-2 diabetes.Imagine a dog learning to fetch a ball. As soon as you tilt your arm back to throw, the dog runs toward the ball. At first, when you pretend to throw – feigning the obligatory arm motion – the dog still takes off in search of the ball.

But after a few fake throws, the dog catches on and waits to see the ball leave your hand before sprinting off. Just like the dog – your body adapts to the consumption of these fake sugars, and thus changes how it processes real sugar. The Swithers lab studies these adaptations.

In rats, Swither’s research shows that long-term exposure to artificial sweeteners alters how the body metabolizes real sugar. A rat exposed to artificial sweetener releases less of a hormone called GLP-1 when consuming real sugar. The GLP-1 hormone controls the speed at which food empties the stomach and enters the intestines. When GLP-1 levels are low, the stomach empties faster, allowing sugar to more rapidly enter the bloodstream. In other words, rats exposed to artificial sweeteners experience an abnormal spike in blood sugar when regular food is consumed.

Artificial sweeteners change human metabolism too. Yanina Pepino, a biopsychologist at Washington University’s School of Medicine in St. Louis, studied how 17 obese subjects processed glucose after ingesting water or sucralose, the most commonly-used artificial sweetener. And she found something surprising. Participants who consumed sucralose before glucose released 20 percent more insulin than when they had water before glucose. The significance of this is unclear. But if artificial sweeteners played no role in metabolism as we previously thought, they shouldn’t influence the release of insulin. Pepino’s lab is now conducting the same experiment with non-obese subjects.

Beyond these labs, research demonstrating that artificial sweeteners negatively alter gut bacteria accumulates (see this, this, this and this). Two of those examples, it should be noted, received industry funding.

These findings add a new dimension to a tremendous amount of conflicting research on diet drinks and body weight. Some studies have linked artificial sweeteners to weight gain in both adults and children. Others report no change or weight loss when diet soft drinks are combined with behavioral interventions.

Conflicting results are largely due to different study designs – some studies monitor their subjects for a short period of time in a lab. In others, subjects report their own food choices over many years in the real world.

But Swithers cautions that some researchers, especially in the case of these long-term, observational studies, are too conservative in their use of statistics, and as a result, may be missing real effects.

“We don’t know that diet sodas cause weight gain, but they could, and so we have to be very careful about not over-correcting for those kinds of things,” she said.

Consider this example. A team at the University of Cambridge studies the relationship between artificial sweeteners and Type 2 diabetes.

The link between real sugar and this kind of diabetes has long been established. But to understand the relationship between artificially-sweetened beverages and Type 2 diabetes, scientists combined data from 17 studies in the US, Europe and parts of Asia. Their results were published on July 17 in BMJ. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption puts a person at a greater risk for diabetes, said Fumiaki Imamura, an epidemiologist and lead author of the study. The verdict on sugar substitutes is less clear.

A note on the studies analyzed by Imamura and colleagues. None of the 17 were funded by industry. These were long-term studies, tracking people for at least six years.

Of the 462,900 people surveyed, eight percent were diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes after starting the study. Close to half the participants didn’t consume any sweetened beverage, the rest were separated into groups based on whether they consumed roughly a cup a day of sweetened and artificially-sweetened beverages.

Getty Images / Bill Boch

During the first round of analysis, researchers found that participants consuming sugar-sweetened beverages were 18 percent more likely to be diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes than participants who opted out of all sweetened drinks. But surprisingly, participants drinking artificially-sweetened beverages also showed a greater risk. Data showed they were 25 percent more likely to get diabetes than those who drank water and other non-sweetened drinks.

At first glance, that appears to be bad news for diet soda lovers. Results looked less grim after researchers controlled for body weight. When they did, the number dropped from 25 percent to 8 percent.

Wanting to be certain of the connection, Imamura and colleagues took a closer look at the data. They concluded that three of the 10 artificial-sweetener studies were biased – showing “unrealistic” results due to improper statistics and using a less-than-ideal population, Imamura said. For example, one study reported the risk of Type 2 diabetes to be six times higher in people that consumed one serving (roughly the size of red bull can) of artificially sweetened beverages a day. But Imamura believed that effect was too strong biologically.

So they excluded the three outlier studies and controlled for obesity. And when they did, the link between artificially-sweetened beverages and Type 2 diabetes vanished, making sugar-sweetened beverages the only health hazard.

But did the researchers, Swithers asked, “throw the baby out with the bathwater?” Remember, Swithers’ and Pepino’s research showed that artificial sweeteners alter metabolism, which could contribute to weight gain. So are we missing something important by controlling for weight?

Overweight people are more likely to drink diet soda in an effort to lose weight, Imamura said. But overweight people are also more likely to develop Type 2 diabetes. He believes the crude findings – that artificial sweeteners are linked to Type 2 diabetes – are muddied by the fact that many of the diet soda drinkers are overweight and predisposed to disease to begin with.

Swithers, on the other hand, says that the crude findings should not necessarily be dismissed as a false positive.

We still need more research to understand what the changes in metabolism from artificial sweeteners mean for body weight. Imamura, Swithers and Pepino do agree on one thing though: there is no solid evidence that diet sodas help people lose weight. Our love for sweetness – real or fake – is more likely the culprit.

“Neither sugar nor artificial sweeteners are necessarily bad, it’s just that we now are in a place where people’s diets contain so many sweeteners that we are overloading our ability to actually consume them,” Swithers said.

Pepino agrees that moderation is the key – and beyond that, “it doesn’t matter which one you use,” she said. But on the rare occasion that Pepino has a sweet drink, she avoids artificial sugar, because, she said, we just don’t know enough.

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2ejmLamusKeZp2hlal6tLvDmmShnZGhwam1xKtkq52Xqrmivoyspp2Z